Scientists now have good numbers to describe the true scale of the world’s biggest iceberg, A23a.

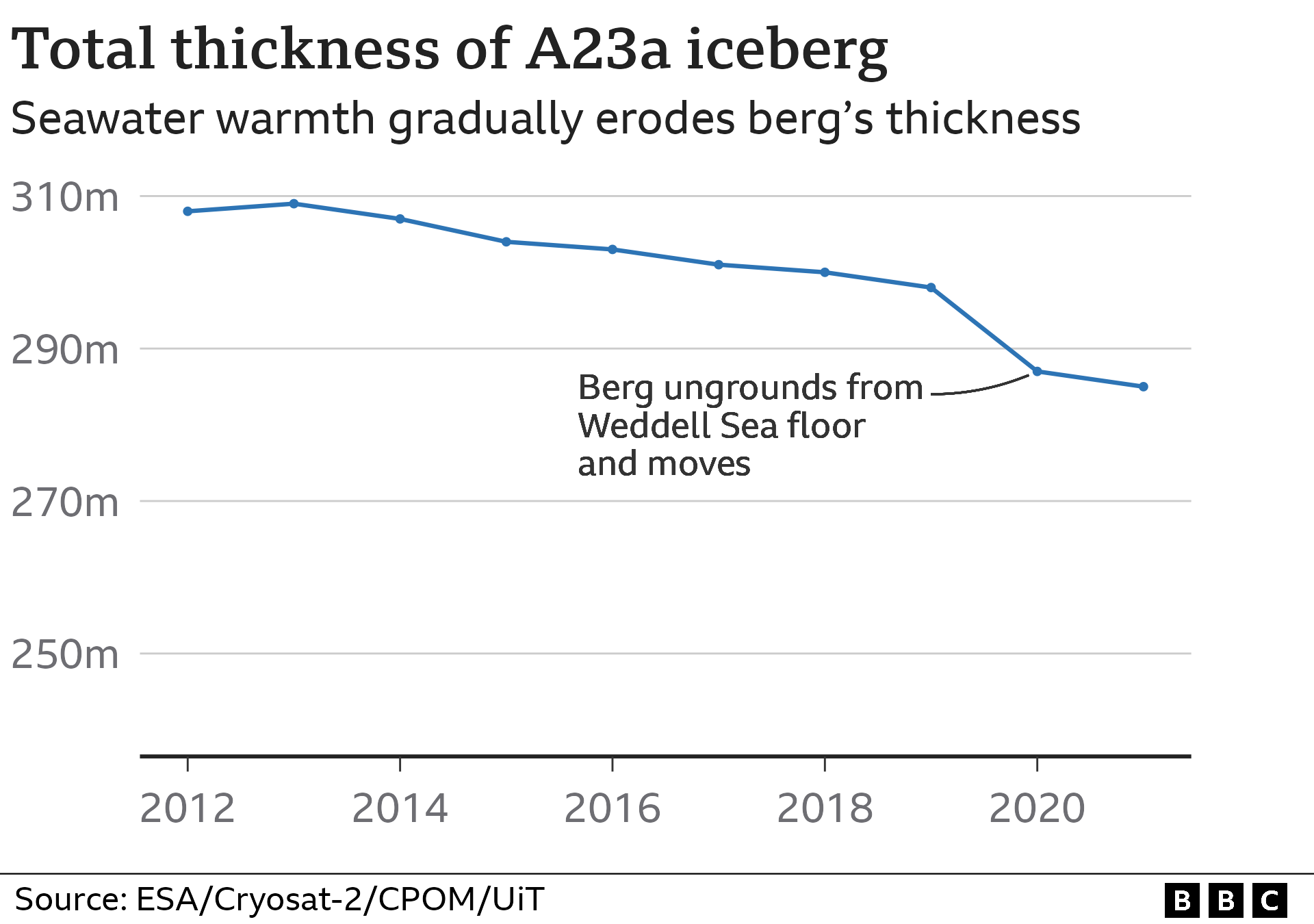

Satellite measurements show the frozen block has a total average thickness of just over 280m (920ft).

Combined with its known area of 3,900 sq km (1,500 sq miles), this gives a volume of roughly 1,100 cubic km and a mass just below a trillion tonnes.

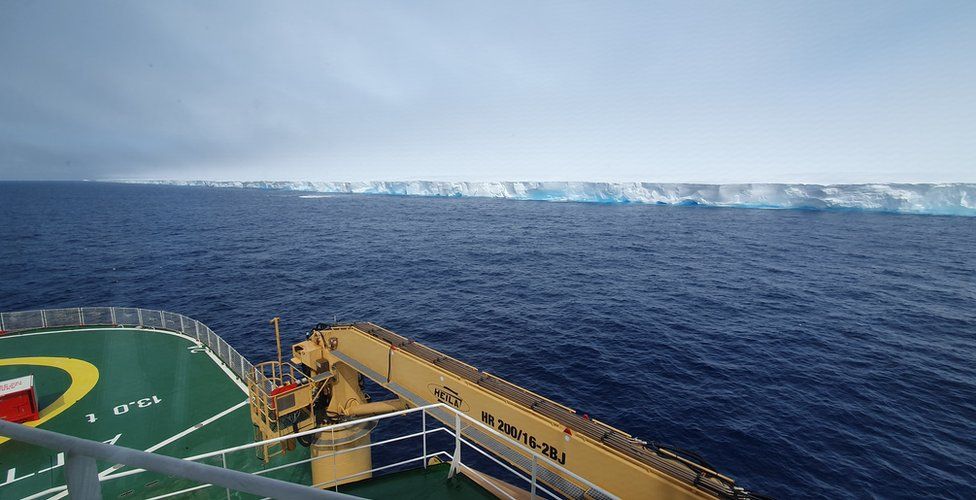

The iceberg, which calved from the Antarctic coast in 1986, is about to drift beyond the White Continent.

It has reached a critical point in its journey, researchers say, with the next few weeks likely to decide its future trajectory through the Southern Ocean.

To put the new thickness data in some context, London skyscraper 22 Bishopsgate is 278m tall – bettered, in the UK, by only the 310m Shard tower.

But A23a is also more than twice the area of Greater London, giving it an overall profile much like that of a credit card.

The measurements of A23a come from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 mission.

This veteran spacecraft carries a radar altimeter able to sense how much of a berg’s bulk is above the waterline.

Using information about the density of ice, it is then possible to determine how much must be submerged.

“Altimetry satellites like CryoSat-2, which measure the distance to the iceberg surface and to the sea surface, allow us to monitor iceberg thickness from space,” Dr Anne Braakmann-Folgmann, from the University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway, told BBC News.

“They also enable us to watch the iceberg thinning as it gets exposed to warmer ocean waters.

“And together with knowledge of the sea-floor topography, we know where an iceberg will ground or when it has thinned enough to be released again.”

When the berg started moving, after 2020, it became increasingly difficult to obtain broad thickness measurements. But assuming an area of 3,900 sq km and an average total thickness of 285m, then A23a has a volume of 1,113 cubic km and a mass of 950 billion tonnes.

Born in a mass breakout of bergs from the Filchner Ice Shelf, in the southern Weddell Sea, A23a was almost immediately stuck in shallow bottom muds to become an “ice island” for more than three decades. And the CryoSat data can now explain why.

The berg is not a uniform block – some parts are thicker than others.

CryoSat indicates one section in particular has a very deep keel, which in 2018, had a draft – the submerged portion of an iceberg – of almost 350m.

And it is this section that anchored A23a for so long.

Satellite images show crevasses directly above the keel.

“This is likely the surface expression of the damage that was caused when A23a hit the seabed,” Prof Andrew Shepherd, from Northumbria University and the Natural Environment Research Council Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM), said.

And in the years that followed, A23a gradually lost mass to eventually free itself and start moving.

“Over the last decade, we have seen a steady 2.5m per year decrease in thickness, which is what you would expect given the water temperatures in the Weddell Sea,” Dr Andy Ridout, a CPOM senior research fellow from University College London, explained.

https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.51.0/iframe.htmlMedia caption,

Watch: The vertical in this 3D model is exaggerated to highlight the very deep keel at one end

A23a has now reached the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where there is a convergence of various streams of fast-moving water that turn clockwise around the continent.

How it interacts with these and the westerly winds that dominate in that part of the world will control where the behemoth goes next.

But it is expected take a track called “iceberg alley” that points in the direction of the British overseas territory of South Georgia.

Scientists will follow its progress with interest.

Bergs this big have a profound influence on their environment.

“They’re responsible for very deep mixing of seawater,” Prof Mike Meredith, from the British Antarctic Survey, told BBC News.

“They churn ocean waters, bringing nutrients up to the surface, and, of course, they also drop a lot of dust.

“All this will fertilise the ocean – you’ll often see phytoplankton blooms in their wake.”

Source: BBC